Happy Thursday! I hope you are having a great day. In today’s post I’d like to share the history behind the piano. Honestly, while so many of us love to play the piano, we do not know how or when it came to be. It’s very fascinating to learn the background of this beloved instrument. It certainly makes me appreciate just how lucky we are to be able to play it in it’s modern form.

Back in 2000 (before I lived in the area), I was very fortunate to be visiting Washington, DC when an amazing exhibit called Piano 300 was at the Smithsonian Institute. This exhibit showcase the 300 years of the piano’s history. I was intrigued by what I learned, and I hope you will be too, as I share my findings in this article.

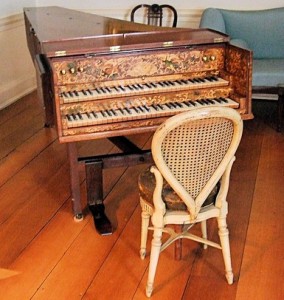

Starting over 700 years ago in the 1400s, precursors of the piano, the clavichord and later the harpsichord, first appeared.

The physics behind each of these instruments is very different from that of the piano. On the clavichord, a brass piece called a tangent presses down on each string making it shorter or longer depending on how high or low the note is. The harpsichord’s strings are plucked (rather than hammered) by a quill.

While these instruments served their purpose hundreds of years ago, they certainly had downfalls. The clavichord player could play with expression, but couldn’t play quietly. The harpsichord player could play loudly, but wasn’t able to add expression to his playing.

While the exact date is unknown, sometime around 1700, an Italian man, Bartolomeo Cristofori invented the pianoforte, the closest precursor to our modern piano. It was the first keyboard instrument that was able to play both soft (piano) and loud (forte), thus the name pianoforte. On top of that it could play expressively– combining the best of both worlds from the clavichord and the harpsichord.

Surprisingly the piano remained unknown for about 11 years until 1711 when an Italian writer, Scipione Maffei, praised the instrument in one of his articles. Right after that more piano makers emerged building pianos similar to Crisofori’s. It’s funny to me that one of the greatest composers, Johann Sebastian Bach, actually didn’t like the piano when he first learned of it in the 1730s. Later on around 1747, Bach finally gave his approval.

Developments were made to the piano over time. The range increased from 5 octaves to the over 7 octaves found on pianos today. An iron frame made the instrument much sturdier. Double escapement action allowed pianists to play the same note in rapid succession, which wasn’t possible previously.

It was around the late 1800s, during the late period of Beethoven that the modern piano emerged. In fact, the piano created by Steinway and Sons in 1885 is virtually the same instrument we love and play today!

I hope you enjoyed this article. Now I want to hear from you! Leave a comment below and tell me one thing you find fascinating about the history of the piano. Subscribe to the newsletter and “like us” on Facebook. Have an outstanding day, and I’ll catch you next Thursday!

Sincerely,

Cassie

{ 0 comments… add one now }